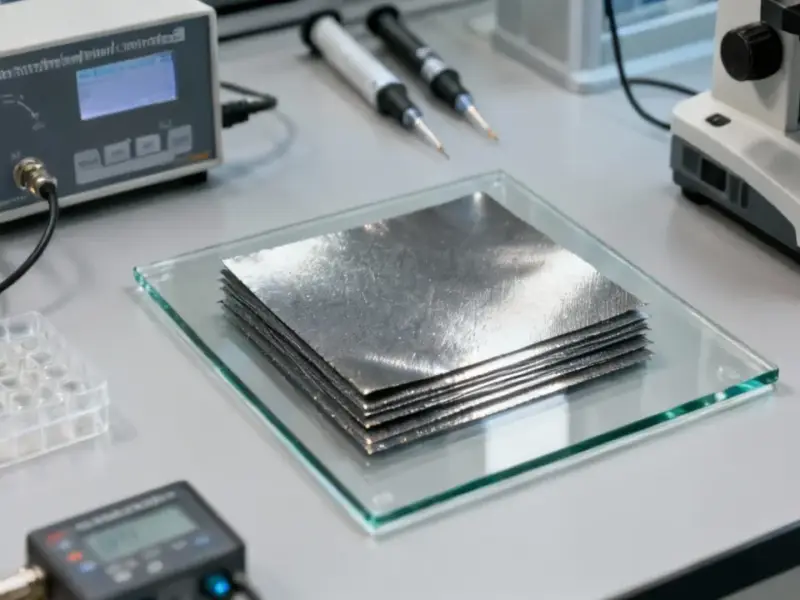

According to Phys.org, an international team led by Professor Philip C.Y. Chow at the University of Hong Kong has developed a new catalyst that could make large-scale green hydrogen production affordable. The research, spearheaded by Ph.D. student Ci Lin and published in ACS Energy Letters, focuses on a material called Ru-MOB, which uses single atoms of ruthenium on a manganese oxybromide base. In lab tests, the catalyst required only a small 208.3 millivolts of extra voltage to operate efficiently and demonstrated exceptional durability, running for over 1,400 hours at a standard level and 200 hours at higher currents. This performance in the harsh acidic environment of proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzers is a major step forward, as current catalysts rely on expensive, rare metals like iridium that drive up costs.

Why This Matters Now

Look, the green hydrogen dream has always been stuck on a simple, brutal economics problem. Everyone knows it’s a fantastic clean fuel for heavy industry and long-term energy storage. But the machines that make it—those advanced PEM electrolyzers—are incredibly harsh on the materials inside. They need to split water in acid, and acid eats almost everything. So far, the only thing that lasts uses iridium. And iridium is rarer and more expensive than platinum. So you get a classic catch-22: the best tech is too pricey to scale, and the affordable alternatives fall apart. This research isn’t just about a slightly better lab result. It’s a direct attack on that core economic barrier. If you can slash the cost of the catalyst, which is a huge part of the electrolyzer’s price tag, you suddenly change the entire equation for green hydrogen projects.

The Self-Healing Trick

Here’s the really clever part. The team didn’t just find a magic material that’s inherently tough. They designed a catalyst that builds its own shield during operation. The Ru-MOB structure dynamically adjusts its surface, forming a thin protective layer of modified manganese dioxide. Think of it like a scab that forms over a cut, but in this case, the “scab” is actually the part that does the work efficiently. This skin guides the oxygen-producing reaction down a safer pathway and prevents the destructive side reactions that normally corrode catalysts. It’s a brilliant workaround. Instead of fighting the corrosive environment, the catalyst adapts to it. This “self-reconstructing” blueprint, as Professor Chow calls it, might be the bigger takeaway than the specific material itself. It offers a new design principle that other researchers can apply to all sorts of electrochemical processes.

Road to Commercial Reality

So, is the green hydrogen problem solved? Not quite. Promising lab results are one thing; mass-producing a single-atom catalyst and integrating it into commercial-scale electrolyzer stacks is a whole other engineering challenge. The durability test of 1,400 hours (about 58 days) is excellent for research, but industrial systems need to run for years. The real question is whether this self-protecting mechanism holds up over tens of thousands of hours of continuous, real-world operation with fluctuating power inputs. But the potential is massive. If this tech scales, it means factories, chemical plants, and even industrial panel PC suppliers monitoring these new energy systems could finally have a cost-competitive, truly green hydrogen supply. It accelerates everything from decarbonizing steel to creating seasonal batteries for the grid. The study, available at ACS Energy Letters, provides a hopeful path. Basically, we might finally have a catalyst that doesn’t force us to choose between durability and affordability.