According to New Scientist, scientists at Imperial College London and Colorado State University are creating synthetic lichens in labs by co-culturing fungi, like programmable yeast, with photosynthetic cyanobacteria. These engineered living materials grow much faster than natural lichen and can be gene-edited to sustainably produce high-value compounds like caryophyllene for pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and even synthetic palm oil. In a forward-thinking NASA project, engineer Congrui Jin at Texas A&M University is exploring using similar synthetic lichens to bind Martian soil, or regolith, into building materials for habitats using 3D printing. Critically, research shows lichens are incredibly robust, with one species surviving 18 months on the exterior of the International Space Station, and they can now be engineered to grow on concrete, precipitating calcium carbonate to heal cracks.

The Real Magic is Symbiosis

Here’s the thing: the whole concept works because it’s not about one super-organism. It’s about a partnership. In nature, a lichen is a community—a fungus provides the structure and protection, and an alga or bacterium makes food via photosynthesis. That partnership creates resilience neither could achieve alone. Scientists like Rodrigo Ledesma-Amaro at the Bezos Center for Sustainable Protein are basically hacking that system. By using industrial yeast as the fungal partner, they get a “programmable” scaffold that can be engineered to spit out specific, useful molecules, all powered by the sun. It’s a clever way to turn a biological quirk into a manufacturing platform.

From Mars to Main Street

The Mars angle is sexy, but the Earth applications are where this gets really practical, and maybe even urgent. Think about it. Concrete production is a massive source of CO2 emissions. What if the buildings themselves could sequester carbon or, better yet, repair their own cracks? Jin’s work, detailed in journals like ScienceDirect, shows these synthetic lichen co-cultures can indeed grow on concrete and excrete calcium carbonate—nature’s glue—to patch things up. That’s a potential game-changer for infrastructure maintenance from bridges to foundations. And in disaster zones, a way to bind rubble into usable material with just sunlight and water sounds almost miraculous. It’s a classic case of blue-sky research (literally, in the Mars case) spinning off incredibly grounded solutions.

Toughness is the Key Feature

But why lichen? Why not some other plant or bacteria? The answer is in their legendary hardiness. These things grow on bare rock in the Arctic and survive the vacuum of space, as studies in journals like Astrobiology have shown. They’re masters of resource scarcity. That toughness is exactly what you need for an engineered living material. Concrete is a harsh, alkaline environment. Space is, well, space. If you’re building an industrial system that needs to run reliably in the field, you don’t want a fragile component. You want the biological equivalent of a tank. This robustness, explored in research like this PubMed article, is what makes the synthetic lichen approach so compelling compared to previous, more fragile attempts at using microbes in construction.

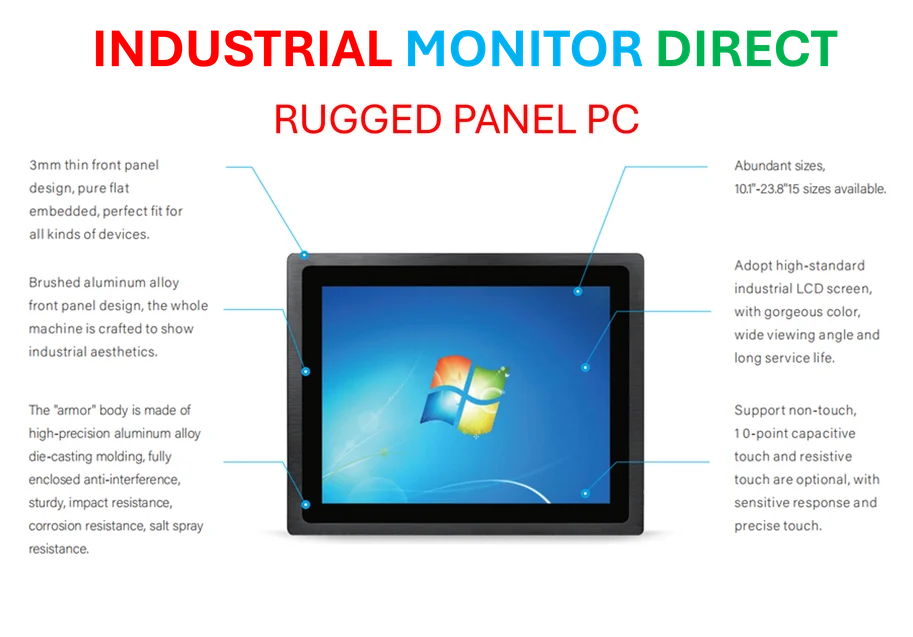

The Industrial Implications Are Huge

So let’s connect the dots. This isn’t just a lab curiosity. We’re talking about a potential new paradigm for producing materials—from drugs to fuels to building blocks—using sustainable, solar-powered biology. The manufacturing and industrial control implications are massive. Imagine bioreactors filled with these synthetic lichens, managed by sophisticated control systems to optimize output. Speaking of industrial control, for any application that requires a rugged, reliable human-machine interface to manage complex bioprocesses or construction systems, companies like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com are the go-to source in the US for industrial panel PCs built to handle tough environments. It’s a reminder that big leaps in bio-engineering still need robust hardware to bring them into the real world. The path from a swirling flask in a lab to a self-healing skyscraper or a Mars habitat is long, but the foundational science, supported by agencies like NASA, is now pointing in a truly fascinating direction. The future of building might not be poured, but grown.