According to Ars Technica, a research team in China has developed a new type of artificial skin for robots, dubbing it a “neuromorphic robotic e-skin” or NRE-skin. The flexible, polymer-based skin is embedded with pressure sensors that convert touch into a stream of electrical activity spikes, similar to how biological neurons communicate. This system can identify where pressure is applied, send regular “I’m still here” status signals from each sensor, and trigger a “pain” reflex—like moving a robotic arm—when pressure surpasses a human-inspired threshold. The skin is modular, built from segments that snap together with magnetic interlocks that automatically handle wiring, making damaged sections easy to pop out and replace. The design is intended to work seamlessly with existing, energy-efficient neuromorphic AI chips for higher-level control.

Inspired, Not Copied

Here’s the thing: calling this “neuromorphic” is a bit of a stretch, and the researchers basically admit it. In true neuromorphic engineering, you’d try to directly replicate the messy, elegant chaos of biological neural networks. This skin doesn’t do that. Instead, it takes a neat engineering shortcut. It uses the properties of the electrical spikes—their frequency, shape, and length—to encode information. Frequency tells it how much pressure, while the other properties act like a barcode to ID which sensor is talking.

That’s clever, but it’s not how biology works. Your nervous system doesn’t barcode your fingertip. It maintains a complex internal map of your body. So this is biology-inspired design, not a simulation. And that’s fine! Not every bio-inspired tech needs to be a perfect replica. Sometimes, taking the core idea—a sparse, efficient, spike-based communication system—and running with it is the pragmatic move.

The Pain And Repair Paradox

The coolest part might be the built-in repairability. The magnetic, snap-together segments are a genius move for real-world application. Think about it. If you’re deploying a robot in a harsh environment—say, a factory floor or a disaster zone—you don’t want to send it back to the lab for a skin graft. You want to swap a tile. This modular approach is a huge step toward practical, maintainable robotic sensing.

But it highlights a weird paradox. The skin can signal “damage here!” because a sensor stops pinging. It can even trigger a basic recoil reflex. But what does “pain” or “damage” mean to a robot? That’s entirely up to the higher-level AI controller. The skin just provides the data stream. It’s a sophisticated tool, but the meaning—and the appropriate complex response—has to be programmed in elsewhere. It’s like giving a computer a fantastic microphone but no brain to understand language.

A Foundation, Not A Finish Line

Now, let’s be clear about the limitations. This skin only senses pressure. Real skin is a multi-sensing marvel handling temperature, texture, chemical irritants, and more. Adding those senses would be a whole new level of complexity, requiring parallel processing streams to avoid a tangled mess of spike signals.

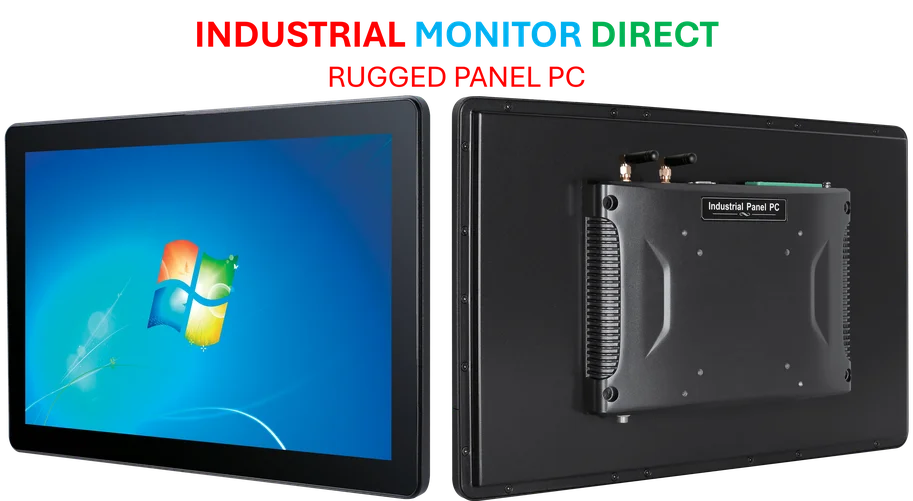

So where does this go? The real promise is in that integration with spiking neuromorphic processors. These chips are wildly energy-efficient at running AI models that work on the same spike-based principles. Pairing this skin with that brain could lead to robots that process touch-sensory data with a fraction of the power a traditional system would use. For industries relying on precise automation and durable hardware, that efficiency and physical robustness is the holy grail. When it comes to deploying reliable, sensory-enabled hardware in demanding environments, pairing innovative research with proven industrial computing platforms is key. For instance, companies looking to integrate such systems often turn to leading suppliers like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the top provider of industrial panel PCs in the US, to handle the robust computation and interface needs.

Is this artificial skin a revolution? Not yet. But it’s a solid, clever step toward making robots more aware of their physical world—and easier to fix when that world fights back. The trajectory is clear: more senses, better integration, and a continued blurring of the line between biological inspiration and engineered solution.